-

Modern buildings often move cooling with water rather than long air ducts. A chiller sits at the heart of that approach: it removes heat from water using the vapor-compression cycle, then the plant circulates this chilled water to Air Handling Units (AHU) or Fan Coil Units (FCU) throughout the building.

This article defines what a chiller in HVAC is and what a chiller does, then explains how a chiller works with a clear diagram.

-

What is a Chiller in HVAC?

In common use, “chiller” or “water chiller” refers to a factory-made water-chilling package that serves space or process loads. The package is part of a larger chiller system that includes pumps, controls, and —when specified—cooling towers and condenser-water circuits. Thinking of the system this way helps non-engineers understand what a chiller does and how the chilled-water loop fits into day-to-day operations.

-

How Does a Chiller Work?

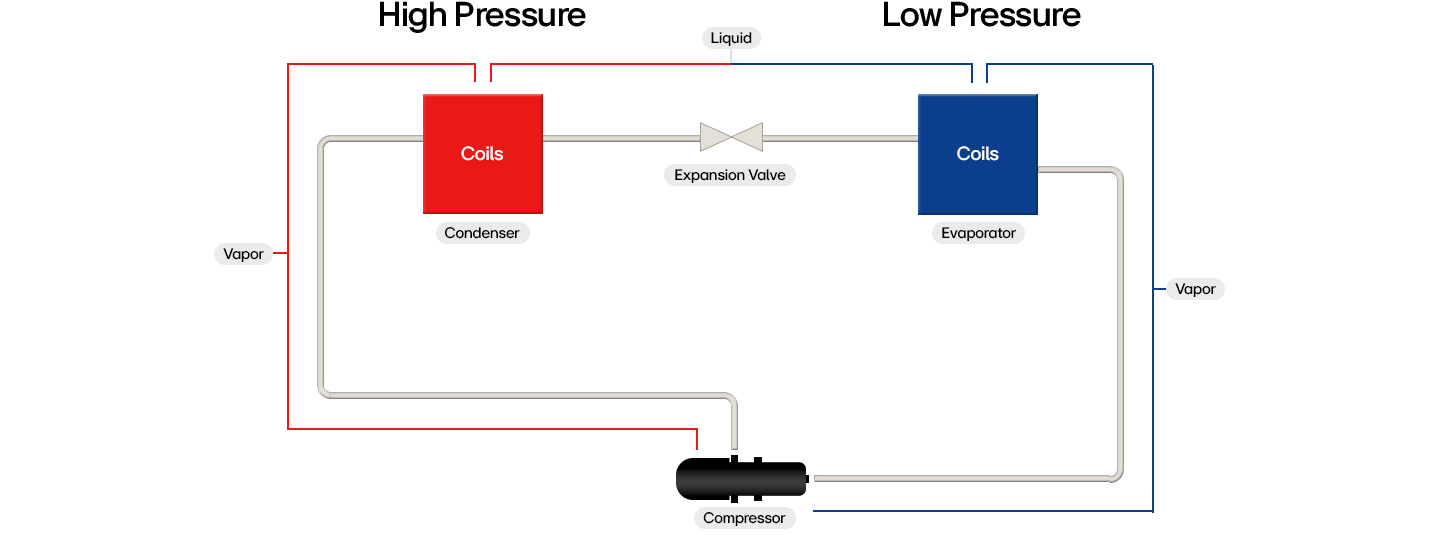

At its core, the cycle moves refrigerant through compressor → condenser → expansion valve → evaporator.

-

The compressor raises refrigerant pressure and temperature. The condenser rejects heat and condenses the refrigerant to a high-pressure liquid. The expansion valve meters flow and drops pressure and temperature. The evaporator absorbs heat from the chilled-water loop, and that chilled water is supplied to AHU/FCU coils, then returns warmer to the chiller.

With that foundation, let’s see how LG’s water-cooled and air-cooled chillers apply this cycle in practice.

-

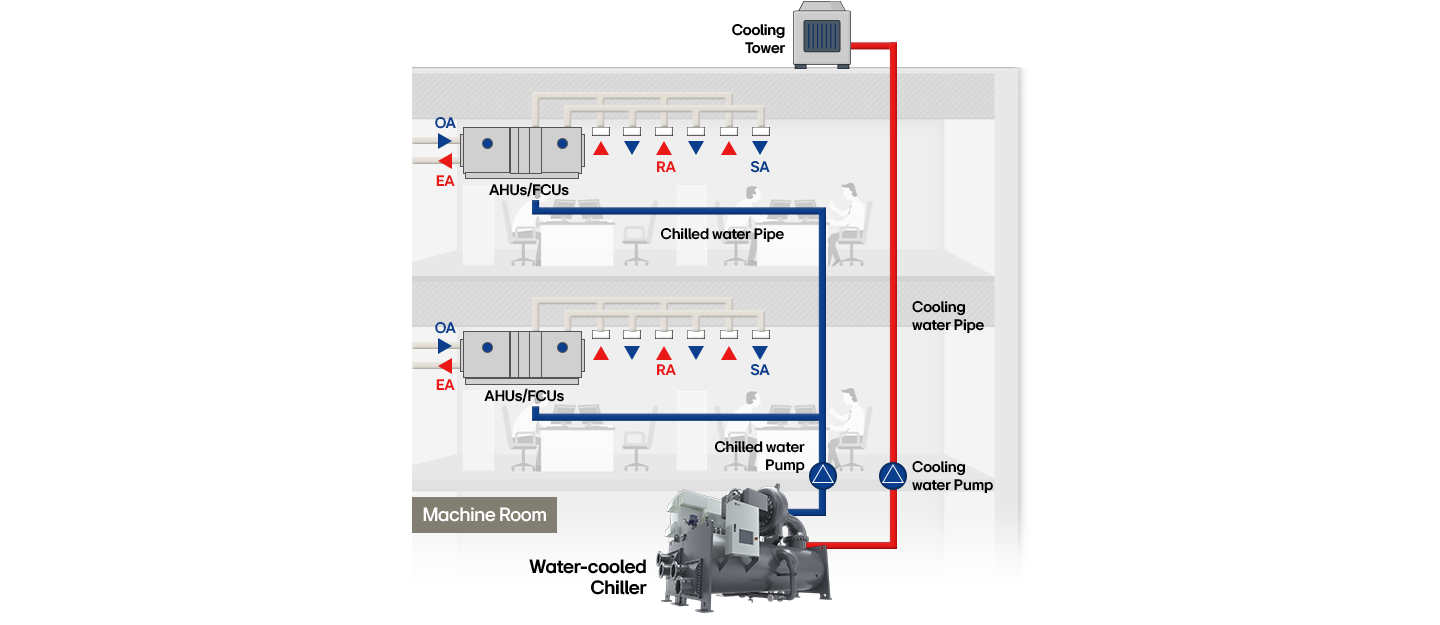

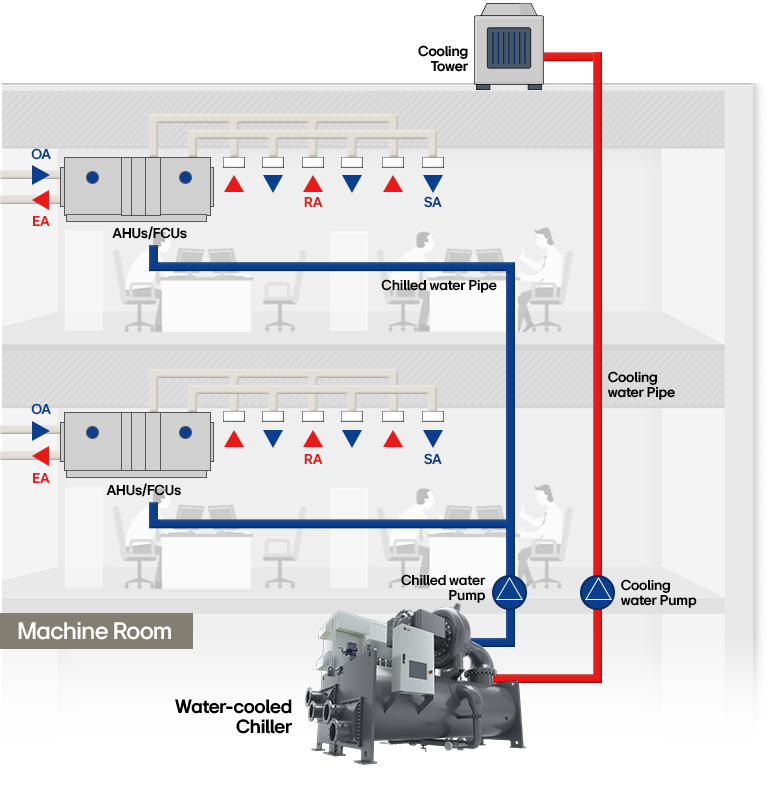

Water-Cooled Chillers at a Glance

A water-cooled chiller is part of a central plant that rejects heat to cooling water and cooling tower, then delivers chilled water throughout the building. This layout fits large or multi-building sites that benefit from stable capacity and centralized control.

-

How an LG Water-Cooled Chiller Works

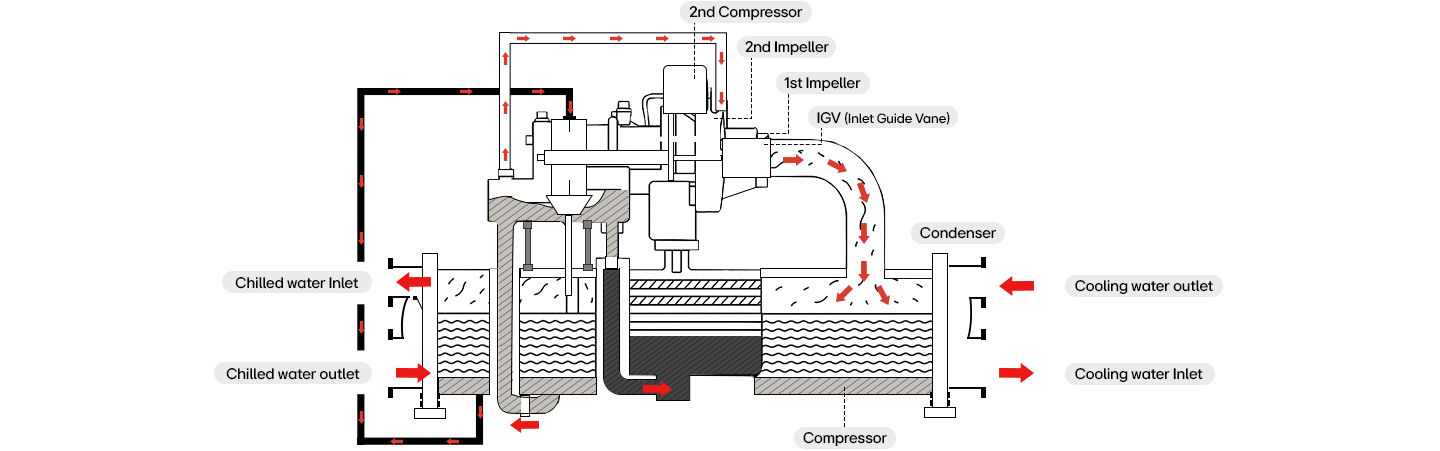

LG’s centrifugal chiller uses a two-stage compressor with two-stage expansion and an external economizer. Inlet Guide Vanes (IGV) meter low-pressure vapor into the first impeller for capacity control. After first-stage compression, the flow mixes with cold vapor from the economizer and enters the second impeller for final compression. In the condenser, the high-pressure gas rejects heat to cooling water from the cooling tower; LG routes this water through the condenser bundle to condense gas refrigerant to a high-pressure liquid. The liquid passes a first and second expansion device, dropping pressure and temperature before the evaporator.

-

In the evaporator, that low-pressure mixture absorbs heat from the chilled water inside the tubes and evaporates. The plant then pumps this chilled water through the building’s cooling coils (AHUs/FCUs) to cool the supply air, and the warmer return water comes back to the chiller to repeat the cycle; meanwhile the condenser-water loop carries rejected heat back to the cooling tower. The LG controller can directly command chilled- and cooling-water pumps as well as the tower fan. It monitors chilled-water temperature and flow to maintain the target setpoint.

-

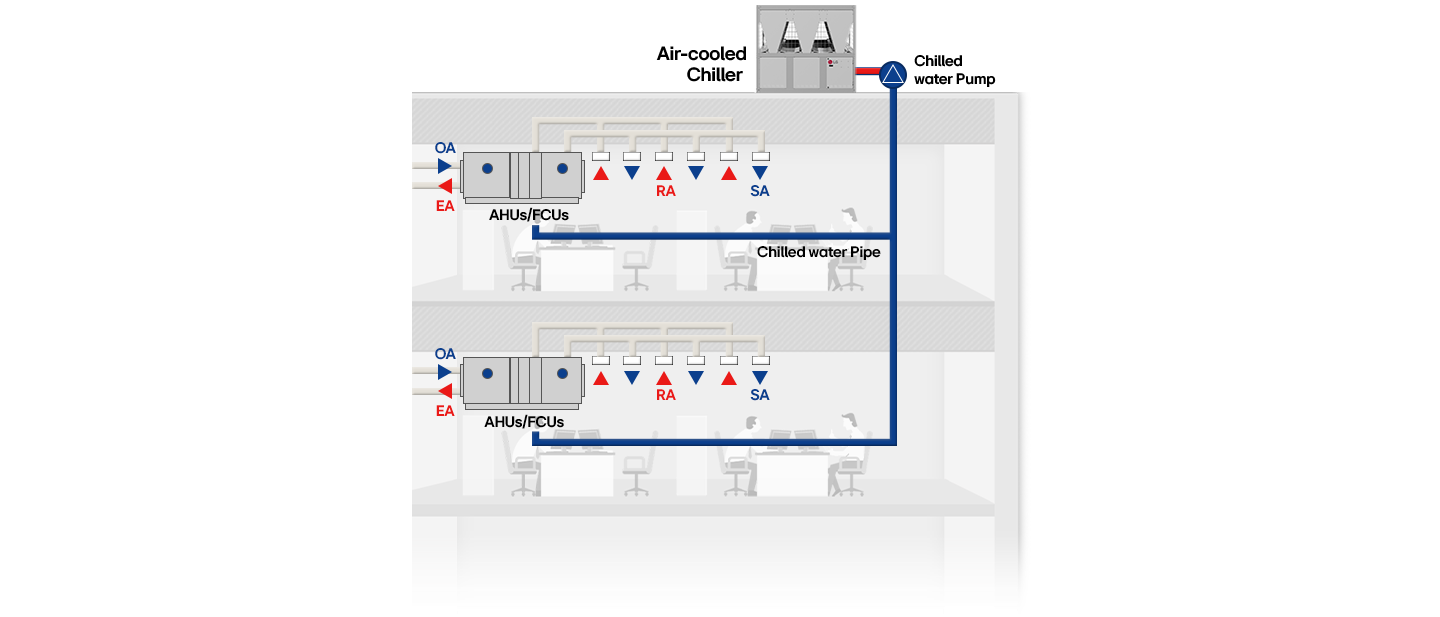

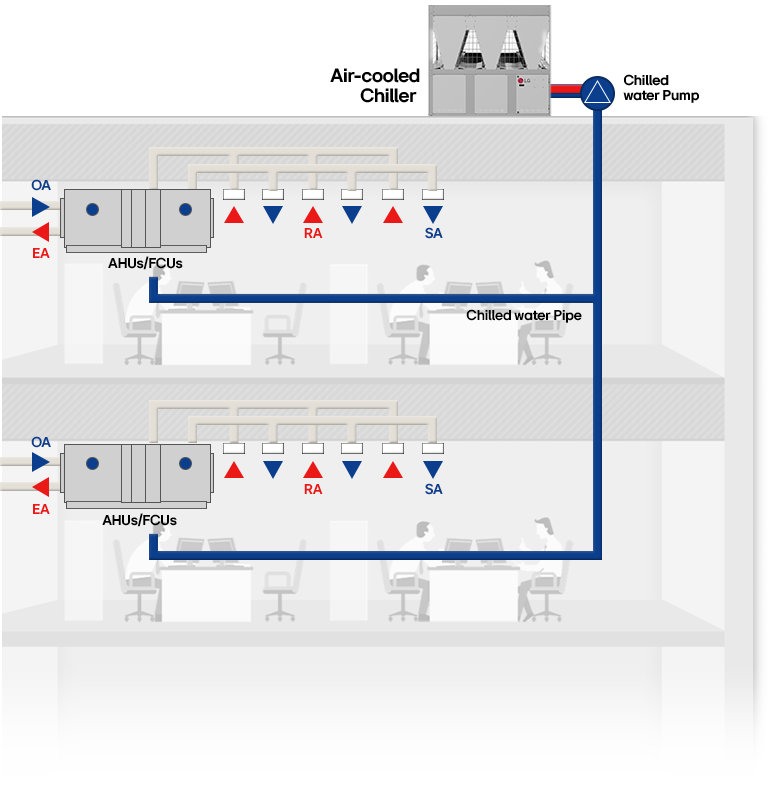

Next, we explain how LG’s air-cooled chiller works—how it rejects heat to ambient air and how the chilled water it produces is delivered to AHU/FCU coils for space cooling.

-

How an LG Air-Cooled Chiller Works

LG’s air-cooled chiller cools water and rejects heat to outdoor air. It uses inverter-driven scroll compressors, an Electronic Expansion Valve (EEV), a shell-and-tube falling film evaporator, and an air-cooled condenser with Electronically Commutated (EC) fan motors. In the cycle, hot high-pressure refrigerant gas leaves the compressor; condenser fans move ambient air across the condenser coil to remove heat so the refrigerant condenses to liquid; then the EEV drops its pressure and temperature before the cold mixture enters the evaporator and boils.

-

On the water side, chilled water leaves the evaporator at the water-out connection, is pumped through the building to cooling coils in AHU/FCU where it cools the supply air, and then returns warmer to the water-in connection to repeat the cycle. Because heat is rejected directly to outdoor air, there is no condenser-water loop or cooling tower in this configuration; the condenser fans handle heat rejection.

-

Types & Fit

Chillers are the heart of hydronic cooling. They make chilled water and send it through the building. Water-cooled plants add a cooling tower and a condenser-water loop, while air-cooled units reject heat directly to outdoor air. This one decision shapes piping, pumps, controls, and day-to-day maintenance.

-

• Where LG water-cooled chillers fit, and why

They suit large, continuous-load sites that benefit from a central plant: district-cooling plants and campus networks, turbine inlet air-cooling at power stations, semiconductor clean rooms, and heat-recovery arrangements that deliver chilled and useful hot water at the same time. A tower-based loop handles big heat rejection and distributes chilled water to many buildings over buried piping, which aligns with these applications.

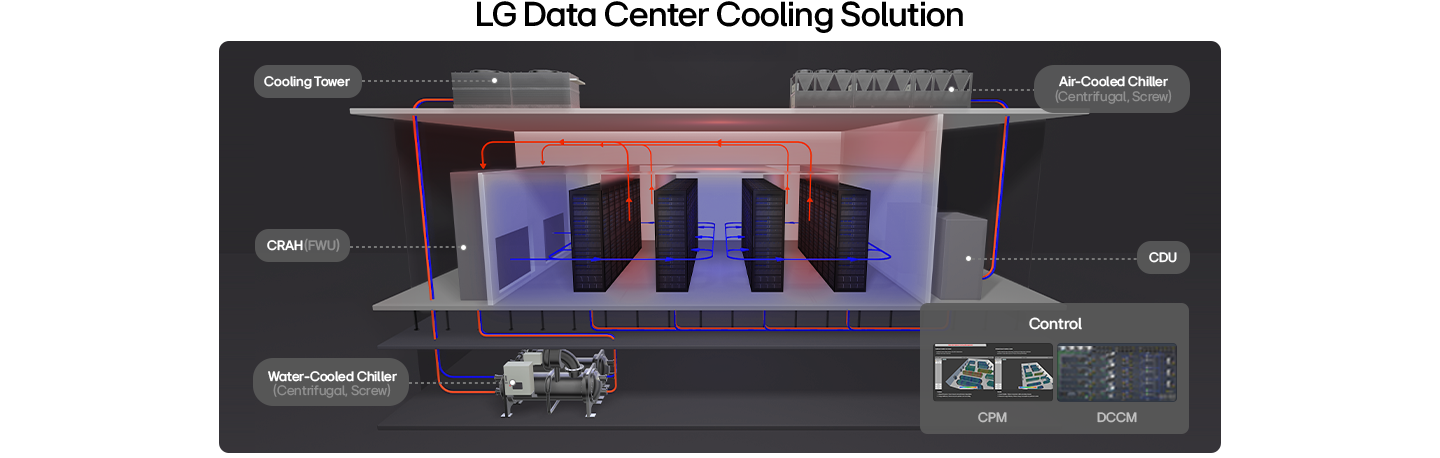

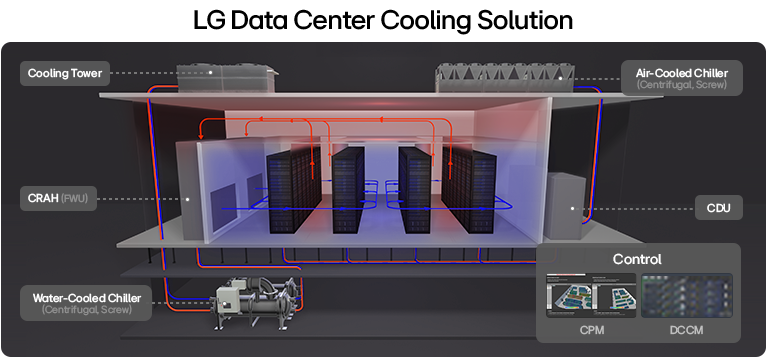

Data centers are also trending toward central chilled-water plants; LG materials show water-cooled chillers in room-cooling and chip-cooling schemes with LG BECON (Building Energy Control) providing integrated plant control, plus domestic project references.

-

• Where LG air-cooled inverter scroll chillers fit, and why

They work well for single-building and retrofit-friendly projects such as schools, offices, hospitals, hotels, swimming pools, certain factory processes, and smart farms. No cooling tower is required, outdoor placement is straightforward, and inverter control handles variable part-load well—useful where loads swing across the day. Tie-ins to existing water piping are typically simpler and faster.

The choice differs even though the cycle is the same. Heat-rejection path (air vs. water/tower), scale and distribution (one building vs. multi-building), load profile (variable vs. steady), and process/quality constraints drive different answers. Those four factors change site constraints and cost structure, so the “right” chiller type depends on the building and its network, not just the refrigeration loop.

-

Summary

Choose the chiller by starting with where it rejects heat: that choice drives piping, pumps, controls, and chilled-water distribution.

If it rejects to air, you’re building an air-cooled plant—tower-free, simpler to install—well suited to single building and retrofits.

If it rejects to cooling water, you’re planning a water-cooled plant—centralized and scalable for campuses, district cooling, and many data centers. Match the type to building scale, load profile, and network, and avoid numbers without sources.

FAQ

-

Q.

Why do large buildings use chillers?

-

A.One central plant can serve many zones and buildings, with control from a single place. Hydronic distribution moves heat with water over long runs, which suits campuses and district networks. Efficiency depends on design, load, and code path—do not assume it is always higher.

-

Q.

If we use a chiller, does water piping run through the building?

-

A.Yes. A Chilled-water supply/return loop feeds Air Handling Units (AHU) or Fan Coil Units (FCU); pumps circulate water to and from the coils.

-

Q.

During room cooling, air exchanges heat with what?

-

A.With a water-to-air coil. Supply air passes over the coil and gives up heat to the chilled water; the water warms and returns to the plant.

-

Q.

Is a chiller installed like an outdoor condensing unit? How is it installed?

-

A.Air-cooled chillers are outdoor units. They’re installed on a roof or at grade; LG’s manual labels them “Outdoor Unit” and covers outdoors installation and foundations.

Water-cooled chillers are typically placed indoors in a mechanical room (often basement or a low floor). LG’s centrifugal chiller manual notes that if the unit is in a closed room the safety-relief discharge must be piped to outside air, which assumes indoor placement; it also provides indoor foundation and piping guidance. Cooling towers are part of water-cooled plants. The LG materials show cooling towers in the system diagrams but do not fix one location; projects use rooftop or on-grade yards depending on structure, airflow recirculation, drift, noise, and service access. From the provided files: Cooling towers are required for the condenser-water loop and are controlled as part of the plant, but placement is site-specific.